by Admin

Op Ed: What’s Possible in Writing About Ballet?

How do we respond to recurring accounts of an acclaimed choreographer’s damaging relationships with dancers, especially women? Recent podcasts (Erika Lantz’s The Turning: Room of Mirrors) and books (Alice Robb’s Don’t Think, Dear) have contributed to a narrative that’s been emerging for decades: Throughout his […]

ran-&-rave

by Admin

Begin Again: Acting for Dancers

It’s my personal belief that at the center of every electrifying dance performance is a story. Even the works that are supposedly plotless have something evocative going on behind the eyes—in the way the body floats, jabs, crumples, and reaches. Sure, dancers tell their own […]

ran-&-rave

by Admin

The Gift of Dance Makes a Great Holiday Present!

Ballroom dance lessons make a perfect holiday gift because of the many benefits they can provide. Not only does dance help people to stay fit and healthy, but it also teaches them coordination, creativity and discipline. It’s a creative and out-of-the-box gift idea AND it’s […]

Ballroom dances

What Heel is Best for You?

by Admin

When it comes to shoes, comfort and performance go hand-in-hand. Possibly the most important component of a dancer’s outfit, the type of shoe and heel you choose is crucial. We’ve compiled a list of heels that suit different needs and dancer preferences. Traditional Heel The […]

Ballroom dancesWhen it comes to shoes, comfort and performance go hand-in-hand. Possibly the most important component of a dancer’s outfit, the type of shoe and heel you choose is crucial. We’ve compiled a list of heels that suit different needs and dancer preferences.

Traditional Heel

Traditional Heel

The traditional dancing heel, known as the “Oxford” or the “Gibson,” is a classic for a reason. With a flat base, suede bottom and a slightly slanted and rounded top, this shoe is stable and durable. However, it trades comfort for durability – you may find yourself getting sore from heavy use.

Rounded Heel

Many ballroom dancers choose the rounded heel shoe for easier movement. This is the perfect heel for dancers who incorporate lots of dynamic movement into their dancing, allowing for higher mobility with a smaller chance of sliding out of control on the parquet. The lifted sole (as opposed to the flatter sole of the traditional heel) allows for a greater amount of control during high-movement dances.

Slanted Heel

Like the rounded heel, the slanted heel has an inclined back to make for easier movement. Instead of a rounded heel, however, it slants with the rest of the shoe. This heel is a great middle ground for dancers who are looking for the freedom of movement of the rounded heel while preserving the sturdiness and look of the traditional heel.

Cushioned Heel

If you’re looking for maximum comfort, then the cushioned heel is the choice for you. Featuring soft rubber between the suede base and the heel, this heel forefronts comfort above all else. It’s also noiseless on account of the cushioning. This heel may feel less stable than other heels for some dancers, but if comfort is your biggest priority, the cushioned heel is the one for you. Beware, though – the soft layer that makes the cushioned heel comfortable wears off quickly.

While this guide may be helpful for understanding what heel suits your dance style, it’s always encouraged to try them for yourself and find what suits you best. Happy dancing!

by Admin

A Brief History of Ballroom Dance

Ballroom dance is a broad term that encompasses a variety of dance styles that are performed in a ballroom setting. These styles include the Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, Quickstep, and Viennese Waltz. The history of ballroom dance can be traced back to the 16th century in […]

Ballroom dancesBallroom dance is a broad term that encompasses a variety of dance styles that are performed in a ballroom setting. These styles include the Waltz, Tango, Foxtrot, Quickstep, and Viennese Waltz. The history of ballroom dance can be traced back to the 16th century in Europe, where it was primarily a social activity for the upper class. However, it wasn’t until the 19th century that ballroom dance began to be formalized and Standardized.

Ballroom Goes Mainstream

One of the most iconic figures in ballroom dance history is Fred Astaire. Astaire was a Hollywood actor and dancer who appeared in a number of musical films throughout the 1930s and 1940s. He is best known for his partnership with Ginger Rogers, with whom he appeared in 10 films. Astaire’s smooth, elegant style and ability to make complex dance routines look effortless helped to popularize ballroom dance in the United States and around the world.

One of the most iconic figures in ballroom dance history is Fred Astaire. Astaire was a Hollywood actor and dancer who appeared in a number of musical films throughout the 1930s and 1940s. He is best known for his partnership with Ginger Rogers, with whom he appeared in 10 films. Astaire’s smooth, elegant style and ability to make complex dance routines look effortless helped to popularize ballroom dance in the United States and around the world.

The Ballroom TV Revolution

In the mid-20th century ballroom dance experienced a resurgence in popularity due to its inclusion in popular culture. The television show “Dancing with the Stars” which started in 2005, has helped to introduce a new generation to the world of ballroom dance and has made it more accessible to the general public. The show features celebrities paired with professional dancers, as they compete against each other in a variety of ballroom dance styles.

In recent years, ballroom dance has also experienced a resurgence in popularity in pop culture, with the success of films such as “Shall We Dance” and “Mad Hot Ballroom.” These films have helped to introduce the sport to a new audience and have made it more accessible to the general public.

Ballroom dance continues to evolve and change with the times, with new styles and variations being created all the time! Today, it is enjoyed by people of all ages and backgrounds, and is a beloved pastime for many.

For more information on the history of ballroom dance, you can check out the following resources:

The International Dance Council

These resources provide detailed information on the history, evolution, and current events in the world of ballroom dance!

by Admin

Jessica He on the Joys of Being a Professional Ballerina

Visualize your favorite hobby—is it drawing, cooking, running? Now, visualize yourself in your element, whether at your desk, in the kitchen or on the trail, and you are totally consumed in your craft, your brain is so focused on the task at hand that external […]

ran-&-raveVisualize your favorite hobby—is it drawing, cooking, running? Now, visualize yourself in your element, whether at your desk, in the kitchen or on the trail, and you are totally consumed in your craft, your brain is so focused on the task at hand that external thoughts are unable to penetrate your intense, but effortless, concentration. Time seems to stop and you are truly living in the moment.

As a child, I found a similar groove in reading. I remember devouring the Harry Potter books and getting in trouble for reading in bed under the covers when I was supposed to be asleep. I was obsessed with the calming feeling that reading brought me, and how words on a page could steal me away to a magical world where anything was possible. Ballet became that escape for me as I got older, and I found a calmness in the daily routine and tunnel-vision focus that it requires.

Starting ballet at the age of 5, I never really saw any other way of life and left home at the age of 14 to train pre-professionally in Philadelphia. I developed in my career and danced with Houston Ballet’s second company, and this all led to me being where I am today: a company dancer with Atlanta Ballet. The hard work that goes into this art form has always captured my focus in a way that nothing else has been able to, and my brain and my body began to crave the flow state of mind that it brings me. When my attention is completely attuned to the movements of my body, the strain in my muscles and lungs falls away and I find a feeling of serenity and an out-of-body experience.

Every day, I chase the headspace that ballet gives me, and my genuine appreciation for the art has only grown. The best moments in our lives are when we are challenging ourselves, pushing our limits in an effort to accomplish something that is hard to attain yet worthwhile. It brings me joy and fulfillment to devote my time, energy and focus to the never-ending goals and challenges that come with being a professional ballet dancer. I have come to appreciate that it is truly a gift to be able to step into a studio and leave everything outside for a few hours, to step onstage and become a different character, and to give audiences the immersive experience of seeing us convey stories and emotions through movement and music. Dancing leaves me feeling ecstatic, inspired and fulfilled—and always coming back for more.

The post Jessica He on the Joys of Being a Professional Ballerina appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

How to Deal With Perfectionism

Perfectionism is a common trait among ballroom dancers. It can be helpful in driving you to improve your skills and become the best dancer you can be. However, perfectionism can also be harmful if it leads to excessive self-criticism or perfectionistic standards that are impossible […]

Ballroom dancesPerfectionism is a common trait among ballroom dancers. It can be helpful in driving you to improve your skills and become the best dancer you can be. However, perfectionism can also be harmful if it leads to excessive self-criticism or perfectionistic standards that are impossible to meet.

There are some things you can do to help control perfectionism and keep it from becoming a problem.

First, try to be aware of when you start to feel perfectionistic tendencies creeping in. If you can catch yourself early on, you can nip them in the bud before they get out of hand. Perfectionistic tendencies include setting unreasonable goals for yourself and constantly comparing yourself with others who you perceive to be perfect.

Second, remind yourself that nobody is perfect and that mistakes are part of the learning process. Perfectionism can lead to a fear of making mistakes, which can actually hinder your progress as a dancer. Making those mistakes can lead you to be more aware of and set realistic goals for yourself.

Second, remind yourself that nobody is perfect and that mistakes are part of the learning process. Perfectionism can lead to a fear of making mistakes, which can actually hinder your progress as a dancer. Making those mistakes can lead you to be more aware of and set realistic goals for yourself.

Finally, you’re not a god. We ask ourselves why we can’t do something perfectly, and the answer is you simply aren’t (and no one around you is) perfect.

If you find that perfectionism is starting to become a problem in your life, it may be helpful to seek out professional help. A therapist can help you understand the root causes of your perfectionism and develop a plan to manage it.

Perfectionism is a common trait among ballroom dancers, but it doesn’t have to be a problem. With awareness and effort, you can control perfectionism and use it to your advantage. Perfectionism can drive you to improve your skills and become the best dancer you can be. Just remember to set realistic goals, accept that mistakes are part of the learning process, and be willing to let go of perfectionistic standards that are impossible to meet.

by Admin

Why Crafting More-Inclusive Immersive Theater Matters

I am a unicorn, so I’ve been told. I can make people feel a certain way, move a certain way and feel validated. I nestle, negotiate and fly in spaces on- and offstage. My role? Making performers, spectators and directorial/producorial teams feel like they belong. […]

ran-&-raveI am a unicorn, so I’ve been told. I can make people feel a certain way, move a certain way and feel validated. I nestle, negotiate and fly in spaces on- and offstage. My role? Making performers, spectators and directorial/producorial teams feel like they belong. This magical work grew out of my lifelong career in postmodern, physical, immersive and dance theater in Europe and in the U.S.

My name is Stefanie Batten Bland. I am an interdisciplinary director and choreographer. An American of African and European heritage, I am a woman of brown tones and reddish-brown bushy, curly hair that has volume and unapologetically takes up space. I’ve lived the better part of my life in spaces that weren’t necessarily designed for me, and yet I’ve thrived.

Being seen for who you are—with casting, lighting and costuming choices that support that—is an incredible feeling. But it is a state with which I have a complex relationship. I grew up needing to negotiate familial spaces and, as such, was always hired as a type of hybrid mover, sprinkled in hybrid genres. I know how a person’s identity is tied to their reality—and how that spills into their work, whether a production is thematically abstract or a fictional narrative.

Inside of ballet, I was an inaugural choreographer for ABT’s Women’s Movement, for its Studio Company in 2019. I see the ballet industry beginning to examine its hiring practices and role-distribution policies. Now, further spurred on by the theatrical justice movement during the pandemic, it is immersive theater’s turn to change patterns as we move with pride into the rest of this century.

Outside of my own work with my Company SBB, I am casting and movement director, as well as performance and identity consultant, for Emursive Productions, the producers of large-scale immersive theater in New York City and across the globe. Immersive work is a form that often engages with being seen and not—through mysterious lighting, enticing characters and stories that center audience members and set them free to chase, follow and choose how close they get to the cast.

However, there is a profound difference between BIPOC immersive performers not being seen by choice and not being able to be seen at all. This is where I come in. I aim to ensure that directors, producers, scenographers and designers dream up shows with a lens of inclusivity. How can they meet diverse performers in auditions, imagine them in all roles, and then make sure audiences can see them, literally? How do light levels, instruments, costuming, approaches to character description and all the other visual cues, from the space to the sound, help performers play their best fiction while living their truth?

Art-making is complex, controversial. I know what I am doing cannot fix everything nor please everyone. This theater practice has been mainly made for and by people of European ancestry. Not to say BIPOC performers weren’t in these shows. But they weren’t centered around us, our tones, our skin bounce. My work inside of Emursive is profound as it shifts what “absence in plain sight” means in this proximity-based work. My weapon of choice is what great performance is rooted in: imagination. I open up our framework of imagining people by how we see them to also include how they see themselves. Our daily life biases are present in all we do, so I start where I see absence.

In our new show, I help develop characters that previously would have been considered supporting roles. (Just think about how BIPOC performers are often cast as exotic, magical or humorous characters who are short-lived or featured for only a few minutes—like the Black kid in the horror movie who gets killed first.) Some of my approaches to moving beyond “traditional” character decks include shifting to BIPOC-centered imagery in lieu of past predominantly white typecasting patterns. Then I explore the first- and second-degree resources (real people, living or dead, who share a character’s bio or archetype similarities) and ensure they are also BIPOC. I focus on finding the best performer for that character.

From the moment a BIPOC performer walks into a space, they/we should feel empowered. During auditions, the hiring process and the special walk to the dressing room, we should feel normal because our space is made for all to succeed. My work centers on putting into practice a majority–minority cultural shift in performance and identity.

In shows that are already up and running—and this is where the unicorn again raises its head—I apply the same techniques to move a production into present/future time, as opposed to the past. I’ve been in these shows myself and noticed as patrons saw me as an “angry Black woman” instead of the character I was portraying. I saw their fear because of my proximity to them—a result of their biases, even though they’d paid to be inside of a fictional theatrical space. It was humiliating to lose an audience at moments when my colleagues of Euro-based heritage did not.

I help shows rework material in ways that simultaneously honor the scripts while addressing the many complicated facets of life here in the U.S. It has been a lonely labor, but now I am seeing immediate changes. I am needed once again for my hybrid sensibilities, and I not only feel good in my skin, but I can ensure all who come after me will feel good in theirs. When I see the success of this work, it is reflected in the performers, the shows and the spectators. It is thrilling. Creating and re-exploring productions in partnership with people of different skin tones makes more performance opportunities for all.

Race is imaginary. The representation of all in our performing arts shouldn’t be. So says the unicorn.

The post Why Crafting More-Inclusive Immersive Theater Matters appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

Jodi Melnick on Her Lifelong Love of Dance

I am deeply, madly, in love with movement. It is one of the great loves of my life, it is my heart. The very unromantic reason why I dance is because it is my vocation, my entire adult life’s work, it is what I do. […]

ran-&-raveI am deeply, madly, in love with movement.

It is one of the great loves of my life, it is my heart.

The very unromantic reason why I dance is because it is my vocation, my entire adult life’s work, it is what I do. But back to the heart…

Since my beginning, my beginning, beginning, I had (and still do) two modes: constant motion and stillness/staring/observing. Skipping, flying, rolling, running, climbing, dancing down supermarket aisles, cartwheeling…that led very quickly to aerial cartwheeling, and front and back flipping was a perfect fit for my childhood as a competitive gymnast. Those big, moving expressions elided into a greater love for dance, tap, jazz, and to my infatuation with gesture. I’m from Brooklyn, grew up in Long Island, and my dad would take me to New York City Center to see Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. I’d watch the dancing scenes from West Side Story and Singin’ in the Rain over and over again, and choreograph my way in and out of the town pool. In college, I was again constantly falling in love with movement—Limón, Cunningham, Graham, then improvisational forms and, boom, I was hooked.

Dancing can be supremely solitary, especially when you love to be alone for hours in a studio, loneliness being a downfall. But with that comes autonomy, individuality and how I learned about myself. It’s strange to spend one’s life dedicated to creating experiences that vanish as soon as they are constructed—but those experiences forever stay with the body.

Dance brings me pleasure, friendship, expands the shimmering relationship between people and collaborators that has shaped my life. It is expressive of the exact time we are in, full of endless potential, trust and teaches me about continual change. It is freedom, it is community, not to be taken for granted. Dance has been generous; more importantly, it has given me a way in which to be generous—teaching, sharing experiences with my students, continues to push my own dancing and choreographic voice.

The dance community is intense and specific. It is how I have socialized myself in the world and learned the most about myself and how I am best productive and honest.

Dance is the experience of adrenaline and melancholy, wildness and restraint, what is beautiful or terrifying, articulate speechlessness. It is constant, vigorous motion that keeps on going.

I like how dance acts as an intensely active process while watching, making and doing, involving a stream of inferences, hypotheses, predictions and anticipations, and changes on a dime according to one’s stream of consciousness.

Dance is where I locate continuum.

Dance is abundant in form, like water.

A stream, river, pool, coming out of a faucet, falling from the sky, the power of a wave, it is forever changing.

Dance is freedom to be led by my instincts, doesn’t have to be logical; movement can be compared to the infinite sensations I am feeling, a cacophony of ideas, all of them coming from movement.

This dancing life is how I feel rich and embrace optimism.

It is the hardest thing I will ever do.

I’m waiting to wake up and not want to be a dancer. It hasn’t happened yet.

The post Jodi Melnick on Her Lifelong Love of Dance appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

Meet Cira Robinson, Senior Artist with Ballet Black

“My growth as a dancer is never over, and that’s one of the many reasons why I still love it,” says Cira Robinson. The Cincinnati native trained under Arthur Mitchell at Dance Theatre of Harlem and joined London’s Ballet Black in 2008. A senior artist […]

ran-&-rave“My growth as a dancer is never over, and that’s one of the many reasons why I still love it,” says Cira Robinson. The Cincinnati native trained under Arthur Mitchell at Dance Theatre of Harlem and joined London’s Ballet Black in 2008. A senior artist in the company, she’s originated roles in ballets by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa and Will Tuckett, toured internationally, and performed for a 100,000-strong crowd with British rapper Stormzy at the 2019 Glastonbury Festival. She’s a force offstage, too: Her 2017 collaboration with Freed of London produced two pointe-shoe skin tones for Black, Asian and mixed-race dancers—Ballet Brown and Ballet Bronze. And on social media, she was candid about a 2020 health scare that created a shift in her “keep-going” mentality. “It’s a phenomenal thing, what dancers do, but we are not superhumans,” says Robinson. “Health needs to be at the top of the list.”

When She Knew:

“Ballet was always something that just clicked. It wasn’t until I did my last summer program at Dance Theatre of Harlem, at 18 years old, that I knew this is what I wanted to do forever.”

PreShow Jitters:

“My dancer mentality wants to hit every step perfectly, but then my human side kicks in and I accept that I’m a professional and I’ve got this—and if I don’t, I better figure it out! Then I Tiger Balm everything, take a couple of deep breaths and leave Cira in the dressing room.”

Making Dance More Diverse:

“Things are happening, but not at the rate that they should. People should want diversity, development and inclusion in their schools and companies—it’s more than having one person of color as a teacher or on the board.”

Collaborating With Freed:

“I had always pancaked my shoes, but even though it’s something that needs to be done, it’s tedious. I went to Freed of London to inquire about having a custom brown shoe made for me, and they told me that I needed to find the proper brown satin for the shoes, so I did. I went to seven different fabric stores before I found the perfect swatch of brown. When I informed my director Cassa Pancho about customizing a shoe, she sprang into action with Freed, and a collaboration was birthed.”

Her Turn as Teacher:

“I try to keep the values, etiquette, and ‘good stuff’ that I grew up with that helped me to navigate through this dance world, but I also know that I have to adapt to this generation of students. There’s a level of respect that should be there amongst the teacher and student, but ultimately, I like to be as appropriately real as possible with the older students while helping to feed the imagination and dreams of the little ones.”

Growing as an Artist:

“Diving deeper into the acting side of the various narrative roles I’ve portrayed in the past five years, I’ve noticed that that’s where I thrive and feel full. Being extremely vulnerable and consumed in a role onstage and being able to take the audience with me every step of the way is what I’m recently most proud of and what I try to bring to everything that I dance.”

The post Meet Cira Robinson, Senior Artist with Ballet Black appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

My Experience With Long COVID Forced Me to Acknowledge the Vulnerability of All Bodies

As a dancer, I have always understood how much I depend on my body. But I hadn’t ever thought about how much my world would change if it functioned differently. I thought I was rather invincible, with my young age, agility and health. Then, one […]

ran-&-raveAs a dancer, I have always understood how much I depend on my body. But I hadn’t ever thought about how much my world would change if it functioned differently. I thought I was rather invincible, with my young age, agility and health.

Then, one day, I couldn’t breathe. Not easily, at least. I became alienated from my body as it failed to do what I wanted and needed it to do. But let’s first back up a bit.

Before I developed long COVID, a collection of lingering negative effects from the virus, I had this subconscious expectation that I would find relief for any suffering I experienced. I have always had privileged access to the world. Being a white Jewish girl from Eugene, a small hippy town in Oregon, I have dealt with the occasional religious microaggression and familial issues, but the world has been available to me.

Last year, after my junior year at Scripps College via Zoom, I spent the summer in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, working on philosophy research and dancing in the city. I had felt bored and empty so often during the pandemic, but that summer I started to feel like myself again. I could finally dance large and uninhibitedly in a studio after over a year spent dancing in my room, banging my knees on the side of my bed. I went out with best friends who’d also migrated to New York City for the summer. Life was good.

Then, like so many others in late July 2021, I tested positive for COVID-19. Although somewhat shocked that I was a breakthrough case, I had a good feeling that my vaccine would save me from serious trouble and that after two weeks, I could return to business as usual.

During those two weeks of isolation, I slept for days. I discovered I had lost my sense of smell after my parents sent flowers. I cried a lot out of loneliness, screamed into my pillow out of anger, and stared into space, stripped and empty. My body had almost immediately weakened, shaky even when I tried to stretch.

On my first day out of quarantine, I tried to purge my body of this virus by renting out a studio to myself in the city. I spoke while I danced, shaking, rolling, sweating. When I left, I was beyond exhausted and felt a deep heaviness on my chest. Maybe that was too much too soon, I thought.

Back in Oregon, I had a week to rest before driving down to Scripps with my parents. I was ecstatic to start my senior year, in person for the first time since March 2020. On the second day of our trip, as I was carrying a lightweight table to the car, I stopped in my tracks, feeling a weight on my chest and the sudden need to sip extra air. I continued a few more steps and stopped again. Sipped more air. In the car, the weight started to feel heavier and my fear grew. I felt thirsty, but for oxygen instead of water. I started to panic, and then to cry. But the crying made it worse, so I practiced stifling my tears so as not to increase my shortness of breath.

My mom kept asking if I wanted to stop at the nearest emergency room. I had never felt so vulnerable; it was the first time I believed that something in my body could fail. We decided to pit-stop at the hospital, and learned that my oxygen levels were okay, above 90 percent, but I still felt pressure in my chest. It was safe to continue on our drive.

Finally, I was back on campus. I didn’t feel close to normal, but I told myself that if I took better care of my health, I would make a full recovery. I tried a few dance classes, but found myself gasping for air inside my mask halfway through. Each time I ignored my pain and pushed beyond my limit, the weight on my chest increased and my intense exhaustion lasted for nearly a week. I started sleeping through my 11 am ethics course and forgot to bring my computer and textbooks to class. I just couldn’t seem to get organized.

When my school doctor referred me to a long-COVID outpatient clinic, I was thrilled. To hear the phrase “long COVID” in regard to my symptoms was a relief because it meant I’d finally get help. On my first day at the clinic, I was observed during a six-minute walk, and my oxygen levels dropped so low that the lung specialist told me to absolutely stop dancing for the time being. Instead, I went to the clinic twice a week to get hooked up to the rolling oxygen tank while I walked at a slow pace on the treadmill, rode the bike at low resistance for 15 minutes and did some minimal arm exercises. I was the only person I saw below the age of 70 with an oxygen tank.

Though I’d mostly stopped dancing, I still had to choreograph a piece as part of my senior thesis that fall. In rehearsals, I tried to command the room with a motivating presence, but I often had to stop speaking to catch my breath, and I couldn’t demonstrate the choreography more than once or twice. We did our best and made something beautiful, but what I produced didn’t feel like me because I wasn’t fully there to produce it.

Not only did I have chronically low energy, difficulty breathing, dancing or walking up stairs, but this seemingly random sickness had now turned the world around me rotten. The putrid scent came on suddenly; it took me a week to realize that it wasn’t the things I was smelling, but that my sense of smell itself had changed. Many savory foods, coffee, smoke and my own body odor had started to make me gag. I would plug my nose at the dining hall. I later found out that my new condition had a name: parosmia.

Even though I was always tired, I resisted falling asleep because when I had nothing to distract me, I couldn’t ignore the heaviness on my chest or the fear, however realistic, that I might have died a premature death.

As I existed in my new state of being, I went through a long period of mourning for my past life, body, mind, smells and movement. I forgot what it felt like to sweat from moving and to be tired at night because I had lived such a fulfilling day.

I had to constantly ask for accommodations (like driving instead of walking to dinner) and to defend why I needed them. I couldn’t directly blame anyone, though. Invisible illness is difficult to remember. And I didn’t always understand what exactly someone could do to make me feel more acknowledged.

Still, there were a few friends who helped me feel less alone, who didn’t seem somewhat put off by my illness—who weren’t uncomfortable staying with it as a topic of conversation, asking questions and trying to brainstorm little solutions. They met me where Iwas, even if that meant sacrificing some of their desires.

This public health crisis has exposed the attitude our country has toward the chronically ill, the disabled, the sick, the dying and the old. Too often we hear sentiments like “It’s only the immunocompromised or elders who are dying from COVID-19. Why can’t they stay home while the rest of us live our lives?” I always knew this mindset existed, but my own health crisis allowed me to see it from a different vantage point.

The attitude is that the chronically ill, the disabled, the sick, the dying and the old are a burden to even think about. That their lives mean less. That they hold us back, instead of teaching us to see more. The truth, though, is that at some pointmost of us will be ill or experience a change in some ability or function, and all of us will die.

It was easy to see how my chronic illness made me weak. But in fact, it has given me immense strength for patience. The self-compassion required for resilience. The sureness in my own abilities, even when I knew I couldn’t yet use them.

The last year has forced me to see my own fragility but also my own humanity. We will constantly change, constantly develop new ways of moving and being. But we must keep trying to face, struggle with and see these changes. We will never escape the vulnerability of our bodies.

The post My Experience With Long COVID Forced Me to Acknowledge the Vulnerability of All Bodies appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

Jerron Herman, Disabled Dancer, On the Power of Gut Feelings

When you return to a piece of choreography after a while, whether rehearsing for another performance or simply reminiscing with old company friends, it’s a kind of performer time-travel. The muscle memory is potent. You are pulled back to the stage with the emotions and […]

ran-&-raveWhen you return to a piece of choreography after a while, whether rehearsing for another performance or simply reminiscing with old company friends, it’s a kind of performer time-travel. The muscle memory is potent. You are pulled back to the stage with the emotions and knowledge and language you had then; you feel the heat of the downstage light. In the present you are connected to the past and your body lies in between, understanding both what you did then and who you are now. I think this snapshot encapsulates why I dance: I’m responding; feeling this fluid body gleefully rebound off of scattered invitations to perform, curate, choreograph. The body holds a time machine, and that experience of travel makes life sweeter.

I respond through my belly. It was there I felt a twinge and knew I should move to New York, knew I should enter my first dance studio, and knew I should perform onstage. It was what convinced me to pursue anything in the first place—the mixture of terror and delight, a weightless moment. It’s the belly that tells you you’re in your lane. Years of churchgoing had taught me the inescapable power of call and response, and how it’s important to voice your recognition. Words must form on your lips and air must push out of your chest to make a sound. There is nothing but movement in call and response, just a matter of degrees. So, I could only—when I think on it—respond with my body when I was invited to dance. This was revelatory and scary, because for years I was troubled by the incongruity of wanting to be an artist but having less than I wanted be available to me as a disabled person, as someone aged 20 just starting out, as someone new. Up until this point, I had strung together swaths of the full picture, enjoying glimpses of nearness to the stage, or a development process, or any variety of artistry.

“Dancing is the physical sign of the ways I say

yes to art every day.”

Jerron Herman

I must say here that I always knew I could dance, not professional combinations per se, but I knew how to be boundless in my movement if only at house parties. Now, after an invited audition, a choreographer was asking me to join her company. Because dance was so audacious, so out there, I had to do it. On one level, I had no reference and therefore little reason to fear. On another level, I had always known how to be free, leaping in and passionately immersed, so there was a deep reference somewhere that would be my guide to successfully be a dancer. For the first years it was pure osmosis, merely absorbing the environment on the job. And then it became love, as I extended my authentic self across the whole environment. I saw myself in a line where thousands of performers precede me and thousands run after, but I’m taking this point in the timeline of dancers, lending my gifts to our ecosystem. It leaves me breathless to think that every opportunity I have is because I responded to one invitation. Dancing is the physical sign of the ways I say yes to art every day. And see how sweet it was to go back in time? Response is magic.

The post Jerron Herman, Disabled Dancer, On the Power of Gut Feelings appeared first on Dance Magazine.

by Admin

What Type of Dress Should You Choose for Your Latin Dance?

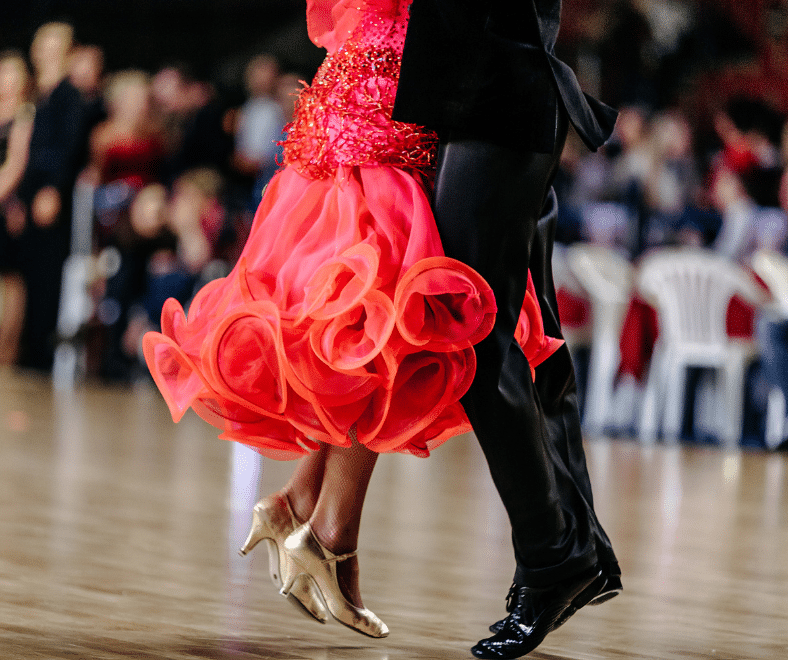

Ballroom dance outfits, especially for the ladies, can range from flirty and fun to graceful and elegant. Latin dance in particular highlights the dancers’ legs and hips, making it more sexy and provocative. But what kind of dresses go well with each of the 5 […]

Ballroom dancesBallroom dance outfits, especially for the ladies, can range from flirty and fun to graceful and elegant. Latin dance in particular highlights the dancers’ legs and hips, making it more sexy and provocative. But what kind of dresses go well with each of the 5 Latin dances?

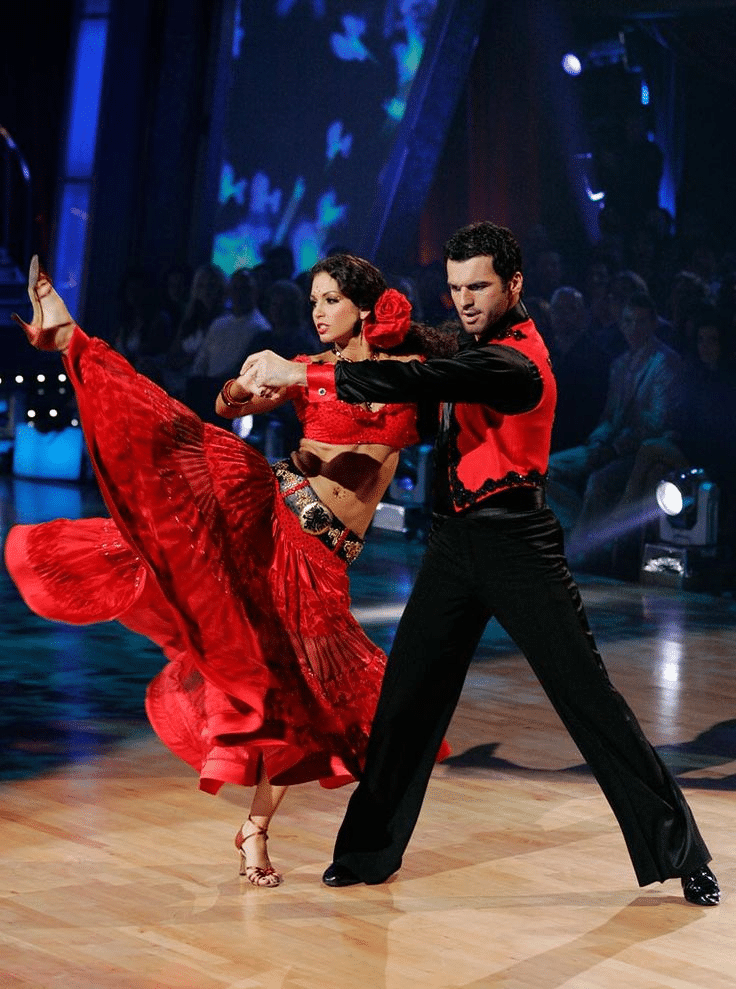

Paso Doble

This traditional Spanish is passionate and desirous. Your outfit should speak to Spanish aesthetics, like adding red or large ornaments or extending the length of your dress. You can also add polka dots, flowers, or epaulets to your dress to mimic the aesthetic of the matador and of the flamenco dancer.

Samba

This dance is all about show and spectacle, and you’re going to want your dress to speak to that. Arguably the most important part of a samba dance is bounce. In order to emphasize the voluptuous movement of a samba routine, we recommend using boa and individual feathers as part of your outfit, especially around the hips. The feathers will synchronize their movement with your own, creating the volume and bouncy effect of the dance.

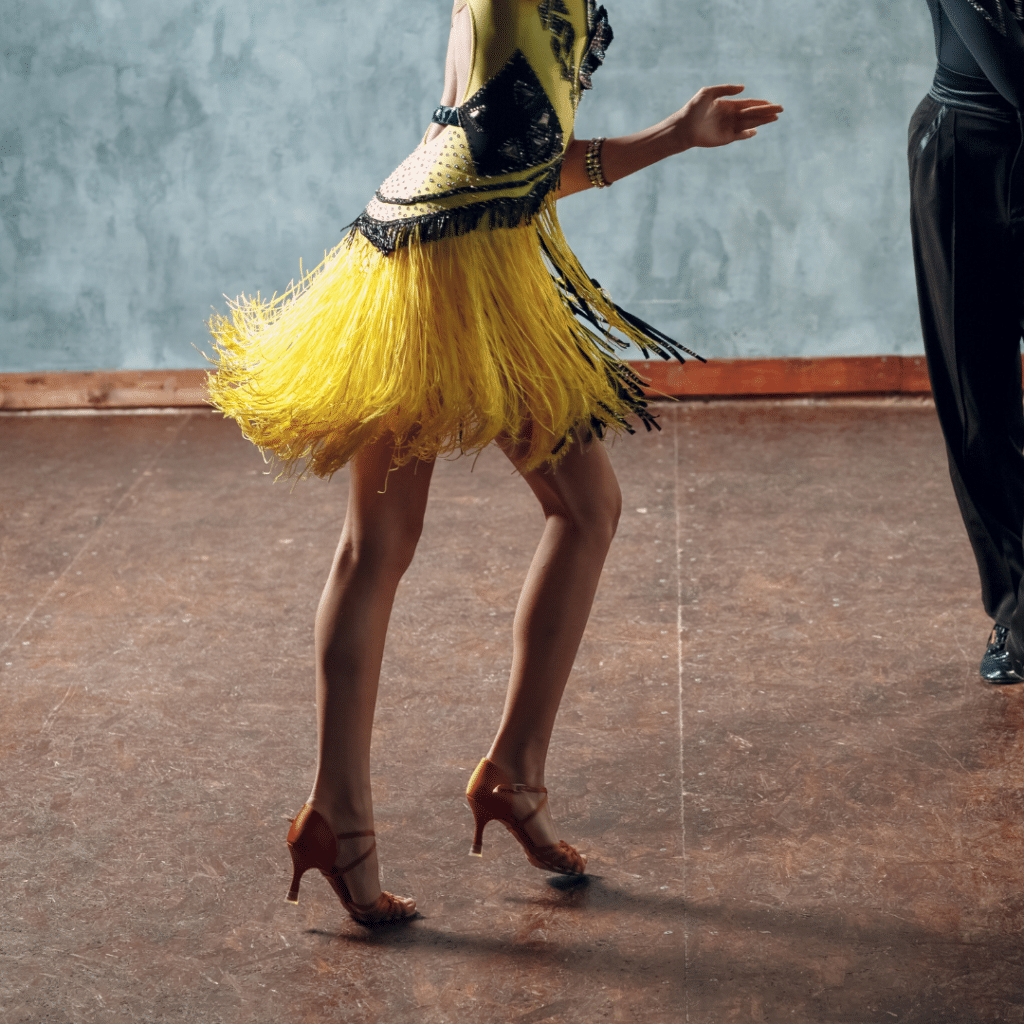

Cha-Cha

One of the more provocative dances, this dance style focuses on hip movement. It’s all about the flirtatious and fun aspect of partnered dance. To forefront the hip and leg movement, you’re going to want bright, fun fringes. It’s suitable to have a short dress for this type of dance, or even a separate top and skirt.

Rumba

Last and certainly not least, Rumba. Rumba is all about sensuality and romanticism. For this reason, your dress should be revealing, but delicately and tastefully. The fluid movement of this type of dance asks for skin-tight outfits or dresses that wrap and hang around your body (consider silk). For a really eye-catching look, we recommend adding crystals to your outfit to make it glitter in the parque light.

With these tips in mind, you’ll find the perfect dress that’s right for you and your dance style for your next routine!